09 Mar Halt the hunt of desert wildlife, say Namibia’s experts

All hunting in the drought-stricken north-western regions of Namibia should be halted pending proper assessment of game stocks, conservationists told John Grobler

Hunting of Namibia’s desert elephants caused controversy last year. During drought, hunting also impacts negatively on core herds of game like oryx and zebra, say the experts. Photo courtesy the Desert Lion Conservation project

All hunting in the drought-stricken north-western regions of Namibia should be halted until a proper assessment of game stocks could be made to judge the impact of three years of drought, legendary conservationist Chris Eyre said this week.

“We’ve not had any decent rain in three years now. The drought has had a very severe impact and there would have been die-offs [of game] that will start impacting on the viability of core herds of larger game like oryx and zebra,” said Eyre.

Villagers in the area have reported that their cattle have started dying because of a lack of grazing, the office of Kunene Governor Joshua //Hoebeb said.

And if domestic livestock was dying of drought, chances were that the game were in an even worse condition, Eyre warned.

The veteran conservationist, who established much of the formal conservation structures in these areas while chief game warden for most of the central northern region during the 1980s and 1990s, said hunting during a time of drought would severely impact on the gene pool.

This could impact negatively on game herds’ ability to recover, as hunting out animals that survived the drought thus far would serve to eliminate the most valuable breeding stocks. Once that happened, chances of the once-plentiful herds ever recovering would rapidly diminish, Eyre warned.

It was therefore necessary to do a proper game count, verified by aerial surveys of especially the Kunene region, to make sure that further hunting by the local communal conservancies and their contracted professional hunters would not push the surviving animals beyond the tipping point, he said.

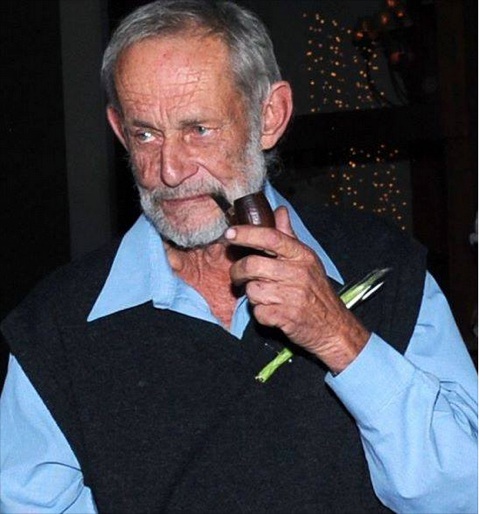

Retired game warden Chris Eyre a few years ago when he was recognised for his lifetime’s contribution to conservation in Namibia. Photo: Tony Figueira

A visit to the area last week showed local people would prefer shooting game for food rather than slaughtering their own animals. With the controversial “shoot and sell” policy still in place, game numbers were visibly declining.

The “shoot and sell” permit system was introduced as part of community-based natural resource management in 2008 to allow local communities to shoot game and sell the meat to local butcheries for a cash income.

Such hunts have to be pre-approved, done by professional hunters and accompanied by a game warden each time.

The reality, however, is that a lack of resources means that game wardens often are not present during hunts, and that permits are routinely issued without the Ministry of Environment and Tourism verifying actual game numbers.

“This shoot and sell permit system is just a form of legalised poaching, a way of making a quick buck at the cost to the entire conservation effort of the past 30 years,” said Duncan Gilchrist, a former Sesfontein chief warden.

Chairman of the Anabeb Conservancy, Titus Rungondo, said that the consensus among many of his colleagues was that the shoot and sell permit system should be removed.

“The game is being abused from all sides,” he said. While the shoot and sell permit system was “not a bad thing” in his opinion, Rungondo said, the indiscriminate shooting of large numbers meant that “… trophy-quality game was being shot for making sausage.

“Hunting for own use should also only be allowed in certain periods,” he said.

The reality, however, was that many conservancies had no natural attractions except game moving across their areas, and hunting was their only source of income, said David Eiseb, coordinator for the Sorris-Sorris conservancy.

The crux remained the accuracy of game counts, which were being conducted in conjunction with the Ministry of Environment and Tourism (MET) on a three-yearly basis.

Critics charged that the count relied too heavily on communal conservancies’ estimates of their game in order to justify ever-increasing shoot and sell permits, which they said were routinely approved by MET’s Outjo office.

In spite of the pressing drought, conservancies were still trying to sell more meat than ever before: a Kamanjab businessman confirmed that Sorris-Sorris had offered him “dozens and dozens” of springbok.

“And I can tell you that I am not the only one they’re offering this to. They need money, and they don’t care if they shoot their last animals to get money,” he said.