26 Nov China’s view on opening trade in rhino horn

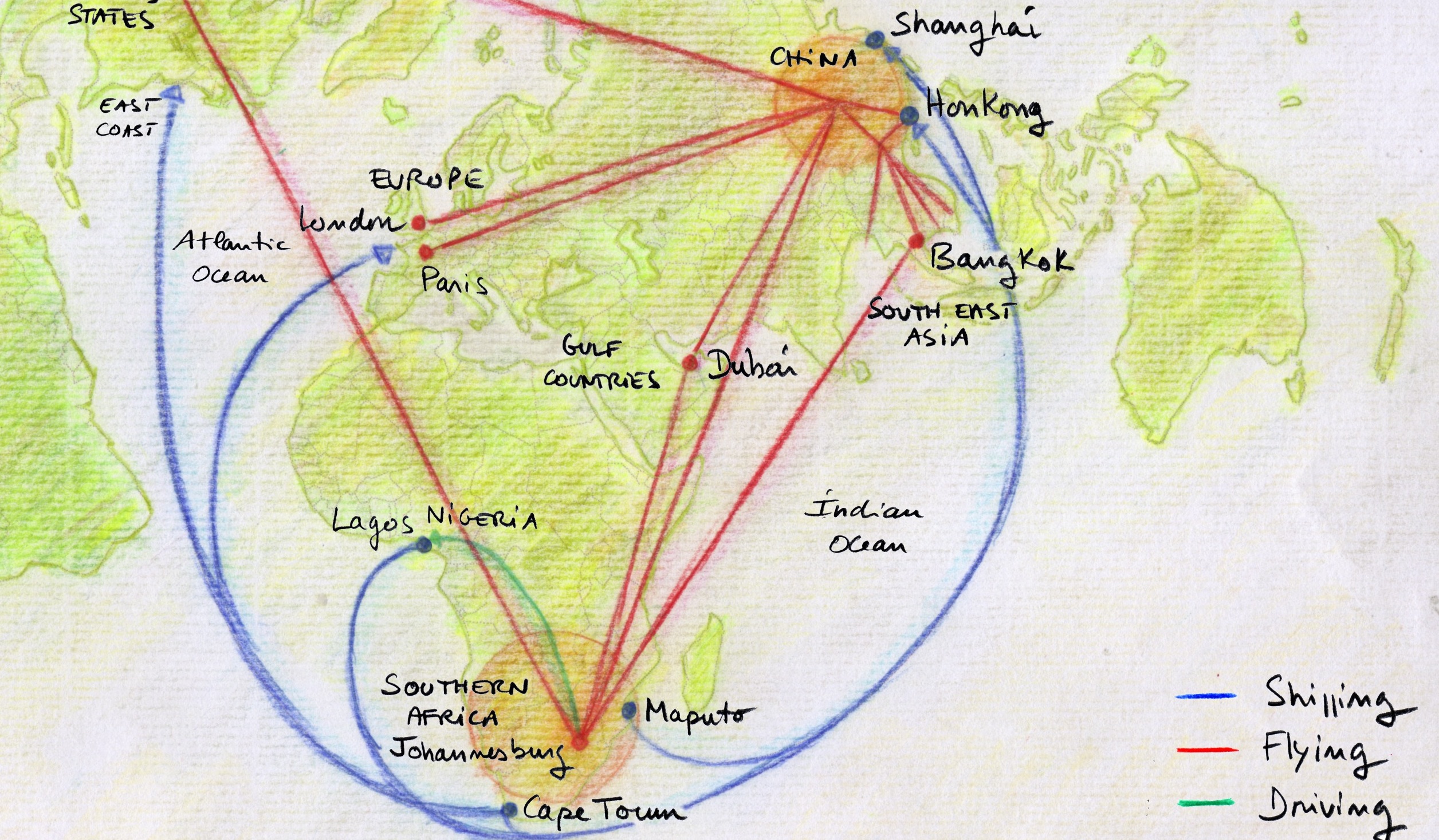

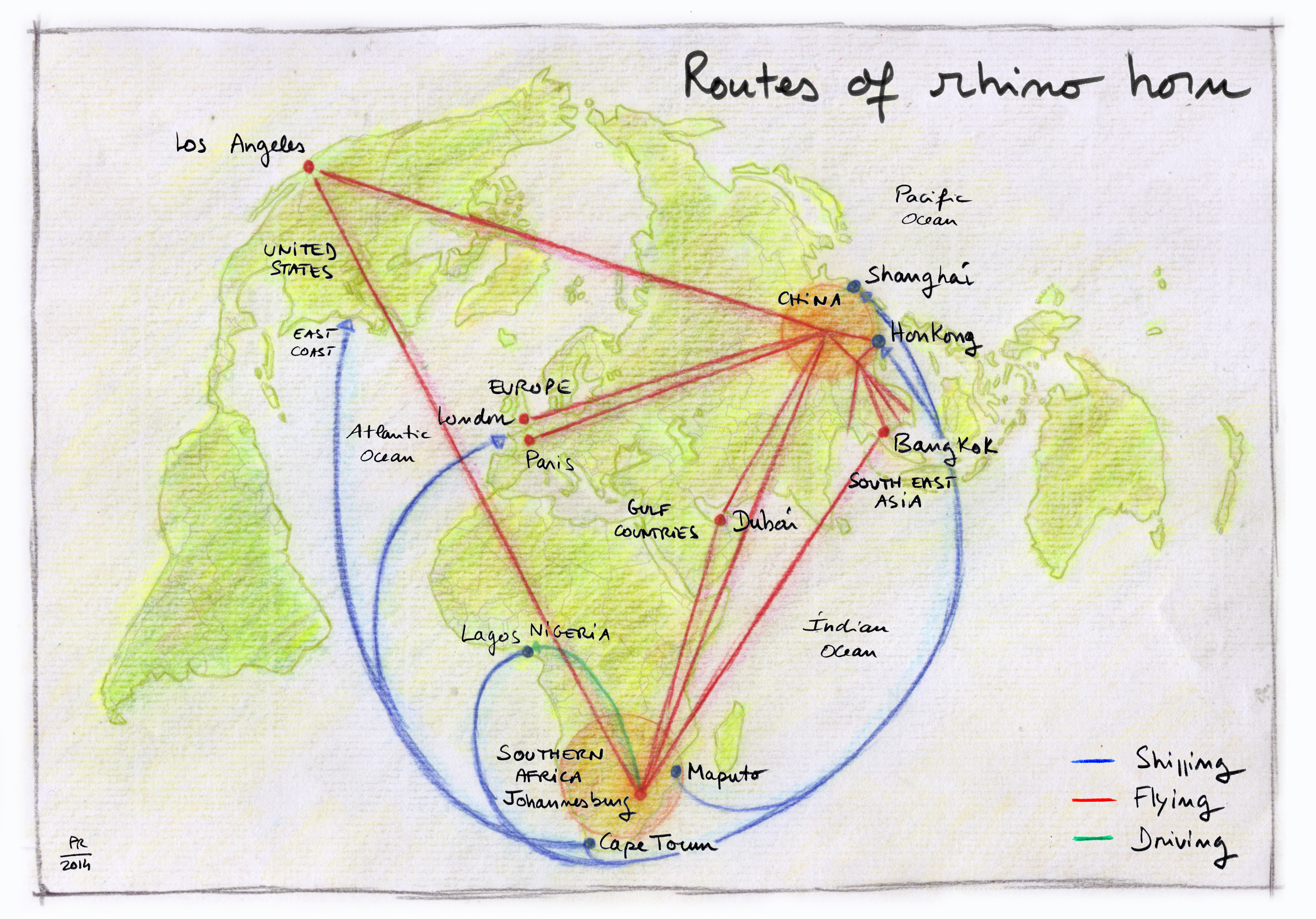

Routes of rhino horn: Illegal pipelines used by traffickers to smuggle rhino horn to China.

Graphic by Philippe Rekacewicz, at visionscarto.net/routes-of-rhino-horn

Wan Ziming, the head of China’s Management Authority at the world wildlife trade body CITES, told Oxpeckers that legalising trade in horns might help to curb poaching of rhinos and the trafficking in horns, but he was concerned that the legitimate horn supply would be insufficient to meet the demand.

“Are rhino horn stockpiles in South Africa enough to meet the demand?” he asked. Wan is the director of the law enforcement and training division of China’s CITES management authority at the State Forestry Administration.

A ban of international rhino horn trade was issued by CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora) in the 1980s and more than 130 member countries worldwide joined the ban in the past 20 years. Since then, no trade in raw horn or any other specimens of rhino, for commercial purposes, is allowed.

However, with an average of nearly two rhinos being killed each day in South Africa, the ban has been criticised as ineffective by supporters of legal trade. Resource economics, private rhino farmers, conservationists and government officials are lobbying for the legal commercial use and international trade between South Africa and other CITES parties.

Legal trade

One of the strongest arguments from the pro-trade group is that the motion is strongly supported by economic models.

Michael Eustace, an independent resource economics is one of them. He has been lobbying for a legal rhino trade for 16 years, and believes that price would control the demand and supply in a legal market. South Africa could provide more than the current level of demand in Eastern markets with horns from natural deaths, old stockpiles and the harvesting of horns by private rhino farmers, he said.

Private rhino owners argue that funds from the legal trade could be returned to conserving and breeding more rhinos, which would help to save the species from extinction.

Side-effects

The economic model and market theory may sound good, say the anti-trade lobbyists, but there is no evidence that prices would decrease. It is more likely that demand, being legitimised, would increase, they say.

A recent consumer study published in September 2013 by the international wildlife trade monitoring group Traffic and the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) backs up the concern. The study shows that, beyond those who currently use horn, there are nearly three times as many people who would use it if they could afford it.

Colman O’Criodain, policy analyst of international wildlife trade at WWF International, said the potential market in Vietnam alone cannot be met sustainably. “In the context of rising poaching figures, legalisation of rhino horn trade would only make matters worse,” he said.

O’Criodain also worries that the price mechanism would one day be out of control. “Even if the horn is sold at an artificially low price, this will not satisfy the aspirations of private rhino owners who wish to recover increased security costs. The price will bounce back up and poaching will continue to be profitable.”

Stakeholders’ opinion

On March 14 2013, South Africa’s Environment Minister Edna Molewa declared her support for a legal international rhino horn trade at the last meeting of the member nations of CITES.

In July 2013, South Africa’s Department of Environmental Affairs published the Rhino Issue Management Report. It made six recommendations on commerce and trade, including the intention to authorise commercial farming of rhinos, to lift the moratorium on domestic trade in rhino horn, and to apply for the lifting of the international trade ban in rhino horn.

According to the report, poaching syndicates are using increasingly sophisticated means to capitalise on the CITES ban in order to supply what appears to be a resurgent market demand. It recommended authorising the sale of farmed rhino horn through auctions on a trading bourse possibly linked to the Johannesburg Securities Exchange.

“The banning of legal, open trade in rhino horn has not resulted in reduced demand for the horn and has thus not helped the objective of saving the rhino from imminent extinction,” said the report.

Will this really happen?

Despite active lobbying from the South African government, government officers in Vietnam and China are more cautious on opening trade. After Vietnam signed a memorandum of understanding with the South African government in December 2012, a new national ban on domestic rhino horn trade was authorised in Vietnam.

In 2016 South Africa will host the next CITES meeting of member countries. At this meeting, South Africa is planning to ask for a once-off sale of rhino horn.

The clock is ticking, and the debate on trade and commercial use of rhino horn is heating up.

“I haven’t seen any signs of any party from CITES that support the motion,“ said Tom Milliken, the head of the elephant and rhino programme at Traffic International.

Opening the trade would require a consumer country to change its national legislation to accommodate the proposed once-off sale.

“With almost every country having banned rhino horn, I have no idea of any country that would be willing to import rhino horn stockpile from South Africa,” Wan said.