03 Dec Exposing India’s secret snow leopard trade

Sadiq Naqvi unveils data and routes behind India’s underground trade in snow leopards and their body parts

Snow leopard at Taklangla Pass in Ladakh. Photo courtesy Pushpinder Singh Jamwal / WWF India

Tipped off about an illegal deal involving a snow leopard skin, an inspector with the Wildlife Crime Control Bureau (WCCB) in India asked for help from the Delhi Police’s crime branch in May 2016. The tip-off concerned a man travelling by bus from Lahaul and Spiti in the Himalayan state of Himachal Pradesh.

Soon after the team arrived outside the interstate bus terminal at Kashmiri Gate in Delhi, the informer pointed out the suspect, who had a grey and black bag slung around his shoulders. The team apprehended a 20-year-old man, Jigmed Ram, and claim to have recovered a white pelt with black spots hidden in a bed cover.

An expert was hurriedly summoned. He confirmed that it was a snow leopard skin, making it the first such seizure in the capital of New Delhi since 2005. It was 48 inches (122cm) from head to tail, indicating it came from a cub.

“It seemed like the skin was old,” an investigator associated with the probe said. “It had lost its glossiness.”

The probe led the investigators to three alleged accomplices in the crime, including a taxi driver from the tourist town of Manali and a teacher from Lahaul who was allegedly the source of the skin.

The case, which is still being tried in court, piqued interest among some conservation agencies after an analysis of the pelt indicated the cat had been de-skinned so that no incisions would show on it. It appeared that the killing of the animal and its pelt had been done to meet an order, they said, and that the skin was being smuggled by cross-border animal hide traders – a worrying new development in the trafficking of snow leopards, which are listed under Schedule 1 of the Wildlife Protection Act in India and as vulnerable by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

“There has to be an incentive for someone to de-skin the animal in this fashion,” said Koustubh Sharma, assistant director of conservation policy and partnerships at the Snow Leopard Trust, an organisation that works to protect snow leopards and their habitat in 12 countries of Central Asia.

“It is not clear if they [the smugglers] are catering to a demand, or if it’s incidental. Smuggling networks are hard to crack for various reasons, including the remoteness of these areas,” said Ajay Bijoor, assistant programme head of the high-altitude programmes at the Nature Conservation Foundation, a wildlife conservation and research organisation based in Mysore, India.

Detection issues

India is home to between 400 and 500 snow leopards, but there is no complete or publicly accessible database of snow leopard crimes in the country (see Mountain ghosts of the Himalayas).

Data collated by Oxpeckers shows at least 43 individual snow leopards have been killed in India since 1994. The WCCB says seven court cases related to snow leopard crimes have been registered between 2000 and 2021.

No seizures or cases of poaching of snow leopards have been reported since June 2016. Officials at the WCCB and a section of experts believe that in many incidents snow leopards are not the target species and that tigers and common leopards are being poached and trafficked to satiate the demand for big cat body parts in Asia.

But the lack of data and seizures does not necessarily mean snow leopards are not being killed.

“I would rather say detection is the major issue,” said Shekhar Kumar Niraj, chief wildlife warden of the southern state of Tamil Nadu who has written a study on trafficking in snow leopards.

“The demand has not come down internationally and there is no significant improvement in protection measures. This species remains threatened due to poaching. It remains underreported.”

Some programmes, like the SECURE Himalaya project funded by the Global Environment Facility, have been initiated to fill in critical gaps and to secure conservation. But India’s snow leopard habitat suffers from a serious lack of manpower on the ground. Officials say they sometimes have just one forest guard to take care of each thousand square kilometres.

Sajid Sultan, a senior forest department official in Ladakh, points out that the Karakoram Wildlife Sanctuary, for instance, has two to three guards to cover 5,000 square kilometres, Changthang Wildlife Sanctuary has four to five guards to secure 1,600 square kilometres and Hemis National Park, which encompasses an area of more than 4,000 square kilometres, has three to four forest guards.

The WCCB itself suffers from a manpower crunch: it has only 15 inspectors for the whole country.

Much of the snow leopard habitat remains understudied. It is only now that a proper survey estimation — called the Snow Leopard Population Assessment in India — is under way to fill in critical gaps in information about the elusive cat.

“This time a very scientific, internationally accepted protocol is being implemented,” said S Sathyakumar, a scientist with the Wildlife Institute of India who is working on the project. “With this current assessment, we will at least know in which grids snow leopards are present.”

Trade and poaching

Besides a lack of information on habitat and population, there is little work on the problems of trade and poaching. “We know very little. Focused work on snow leopard poaching and trade issues has not happened,” Niraj said.

Saket Badola, who heads Traffic India, rues the lack of data. “The majority of data depends on seizures. The seizures we know are not directly linked to the magnitude of the crime,” he said. “There are several other functions required for this data: the extent of law enforcement, how effective it is, and thirdly how many of the seizures are being covered in media and official documentation.”

Research has indicated that a large section of snow leopards that end up in illegal trade remain undetected. Monitoring illegal trade in snow leopards: 2003-2014, a research paper co-authored by Niraj with Aishwarya Maheshwari, now assistant Professor, Wildlife Sciences, at the Banda University of Agriculture and Technology, noted 88 records of snow leopards in illegal trade. However, these figures did not correlate to records maintained by enforcement and other agencies, they added.

“Trafficking of snow leopard parts is highly secretive and underground,” said Maheshwari, who travelled in many of the range countries and scouted the markets.

“If recently we haven’t seen any body parts being seized doesn’t mean the trade has stopped,” said Tito Joseph, programme manager at the Wildlife Protection Society of India, an organisation that has maintained records of seizures and killings. “Data shows snow leopard parts were seized from the Sansar Chand gang and other traders in the past.”

He was referring to the seizure of a snow leopard skin in 2005 from a basement in Delhi’s Patel Nagar area from Narayan Chand, the brother of Sansar Chand, a notorious wildlife trafficker who died of cancer in 2014. In the raid, the officials seized two tiger skins, 38 common leopard skins and one snow leopard skin.

Snow leopard skins have been part of bigger seizures involving other species like tigers, common leopards and red foxes. At least in two instances, narcotics have also been found on the traffickers.

Like other big cat species, snow leopard body parts make their way through the same smuggling routes. “The trade routes are the same, the destination is the same and the buyers are the same set of people,” said Joseph. “It mostly moves via trans-Himalayan routes. Even for narcotics and arms, the players may be different, but the routes are the same.”

Trade routes

Reports, seizures and market surveys show that snow leopard skins from India have found their way to Nepal and China – two countries with long borders with India. This has also been revealed in other #WildEye Asia investigations from Nepal and China.

Trafficking routes from India to Tibet via Ladakh were rampant in the 1990s. “Then body parts including skins would be trafficked to Tibet,” Joseph said.

At the time the fur trade was thriving in Kashmir. In 1997 furriers reported a total of 129 snow leopard items to authorities as part of a government scheme, including 98 skins, 16 snow leopard coats, six mounted skins, one head and eight hats and gloves, a Traffic report noted.

Analysis of some of the more recent seizures indicate that snow leopard skins and have continued to make their way to Nepal and Tibet over the past two decades.

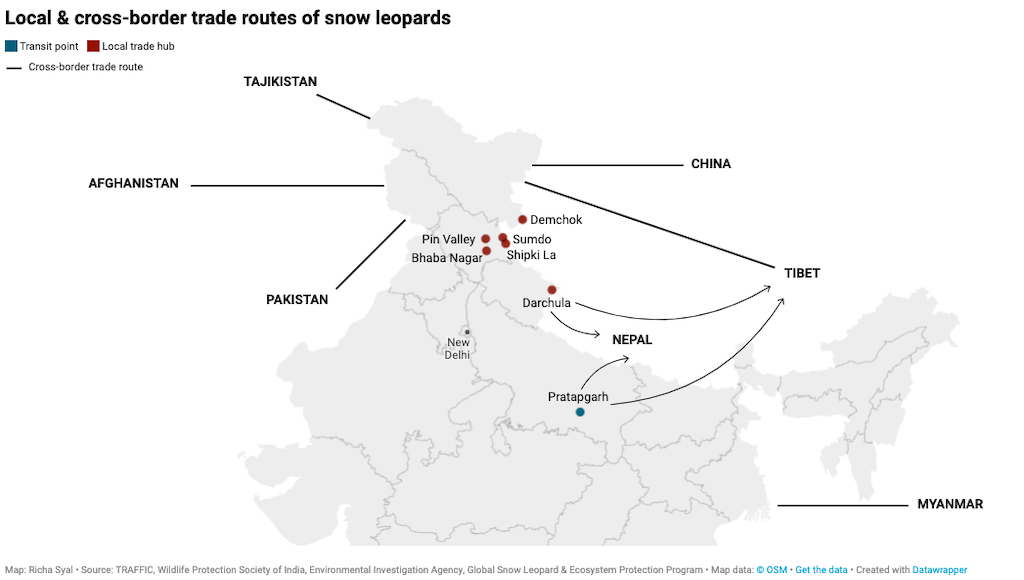

Cross-border routes for the illicit trade from India include to Myanmar and Nepal, and some trade takes place across borders to China, Afghanistan, Pakistan and possibly Tajikistan, according to the Traffic report of 2016. In India, the illicit trade flourishes in Bhabha and Pin valleys, Shipki La, Sumdo, Demchok and Dharchula.

Experts like Niraj believe that as a result of heightened enforcement and criminal conviction rates in China (see China’s snow leopard crimes), it’s likely that the skins and body parts are going via new routes developed on the north-western side of India, from where they are smuggled into West Asia and Europe.

Predator-proof corrals help to minimise livestock losses caused by snow leopard predation. Photo courtesy Rigzen Dorjay / Nature Conservation Foundation

Human conflict

Snow leopards are notorious for attacking livestock pens. Local conservationists point out the corrals are meant to keep the livestock in, but are not designed to keep the predators out. Once a snow leopard enters a livestock pen, it usually causes mayhem.

“Retaliatory killings from farmers who lose livestock is the main threat,” said Tsewang Namgail, the director of Snow Leopard Conservancy, an organisation that works to engage and incorporate local communities in protecting snow leopards in their range states.

About 68% of snow leopard killings in India were retaliatory and another 17% were non-targeted or accidents, according to Traffic. The investigator associated with the probe of the 2016 Delhi seizure suggested it was a case of retaliatory killing, though he refused to divulge more details citing sub judice rules due to the pending trial.

In early May 2020 a snow leopard was captured in Himachal Pradesh’s Spiti after the killing of at least 40 sheep in the preceding four days. It later turned out that the forest department had captured a cub instead of the mother. The cub was released a few days later.

In Ladakh six snow leopards were caught and kept in the forest department’s rescue centre after they came into conflict with human habitations from March to May 2020, while the country was under a strict Covid-19 lockdown.

“There is a lot of conflict. That is the main challenge,” said Khenrab Phuntsog, who works as a wildlife guard in Ladakh’s Hemis National Park. The conflict intensifies in winters when the cats come down the mountain ranges closer to human habitations.

Various organisations have worked on strengthening the corrals to minimise livestock losses. And in cases where there are casualties, forest department officials say they are quick to compensate. “Our target is to compensate them with 50% of the value of their losses,” said Sajid Sultan, a senior forest department official in Ladakh.

A community meeting to discuss predator prevention with herders of Rupshoo. Photo courtesy Vindhya Jyoti / Nature Conservation Foundation

Changing mindsets

Growing snow leopard tourism in Ladakh and Himachal Pradesh has also led to a change in mindsets. Local entrepreneurs in the business say things have transformed in the past decade.

Stanzin Gurmet of Snow Leopard Trails said tourism picked up from 2009-10. “Until then it was thought that it was impossible to see snow leopards,” he said. “But as people started coming and photos made their way to social media, things picked up.”

More tourists has meant more work for the locals. “Now their ponies are deployed to help tourists and the boys work as guides,” Gurmet said.

Snow Leopard Conservancy’s homestay programme now has around 200 homestays spread over 40 villages of Ladakh. “The earnings from tourism help offset livestock losses,” Namgail said.

“The people now know that they have a bigger stake in protecting the snow leopard,” Gurmet said, adding that this has had an impact on reducing conflict.

But experts who study trafficking claim that retaliatory killings continue to go unreported. The many databases which have records of snow leopard seizures and killings only have two records of retaliatory killings in more than the past two decades.

“Getting information [about these killings] is difficult,” said an expert with Traffic India who is not authorised to speak to the media. “Nomadic communities are very tightly knit,” he said, explaining why most of these killings go unreported.

Often the carcass is disposed of, said Jose Louies, deputy director and chief at the crime control division at the Wildlife Trust of India. “Once they kill it, they burn it because they don’t want to be caught by forest officials or paramilitary forces.”

Sadiq Naqvi is an independent investigative journalist based in Northeast India. This investigation is part of a series on illegal trade of snow leopards, supported by Oxpeckers Investigative Environmental Journalism and the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organised Crime.

Find cases involving snow leopard crimes in India and elsewhere on our #WildEye Asia tracking tool