26 Nov Tracking the ‘mountain ghosts’ of the Himalayas

Scattered data is complicating efforts to protect snow leopards against illegal trade, Varsha Singh reports from Uttarakhand in northern India

Rare sighting of a snow leopard in the Western Himalaya Gori Valley. Photo courtesy Rishi K Sharma

Snow leopards are known as the “mountain ghosts” of the Himalayas, living in inaccessible, icy and uninhabited mountain ranges about 3,000m above sea level.

In the state of Uttarakhand in northern India, it is almost as difficult to get a glimpse of these creatures as it is to gather information about them.

For the conservation of snow leopards in the Himalayas, projects like the Global Snow Leopard Ecosystem Protection Programme bring together range country governments, international agencies, civil society and the private sector.

Despite this, crime and poaching data related to this elusive cat has not been compiled in one place – even though snow leopards are listed under Schedule 1 of the Wildlife Protection Act in India and as vulnerable by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), meaning that the species is threatened with extinction unless the circumstances that are threatening its survival and reproduction improve.

The Special Task Force reported seizing this snow leopard skin in Dehradun on December 5 2012. Photo courtesy inextlive

High security

There are no boundaries or borders for snow leopards living in the snowy mountain areas of the Himalayas. But there are several international frontiers, and the deployment of the Army, Border Security Force (SSB) and Indo-Tibetan Border Police in Uttarakhand leads to high security in the region.

Information collated from Traffic India, the Wildlife Protection Society of India, the Dehradun Police and local media reports indicates that at least 10 snow leopard skins were recovered in Uttarakhand between 2000 and 2012, and at least 10 criminal cases were held. However, the Uttarakhand Forest Department, in response to a request for information under the Right to Information Act, said only one skin had been seized during this period.

The SSB reported one snow leopard skin seized in Pithoragarh in March 2012, and in December 2012 the Special Task Force reported seizing a skin in Dehradun. The disadvantage is that, because the agencies that took action in these matters are different, their data is scattered and disconnected.

The presence of the mountain ghosts has been witnessed in the high Himalayan regions of Gangotri National Park in Uttarkashi, Nelang Valley, Nanda Devi Biosphere Reserve of Chamoli and Pithoragarhin Uttarakhand.

According to Dr S Sathya Kumar, a scientist at the Wildlife Institute of India in Dehradun, there are an estimated 85 snow leopards in Uttarakhand and between 450 and 500 in the whole of India. A census of the cats is currently taking place in the country and is expected to be completed by March 2022, he said.

Trade and transit routes

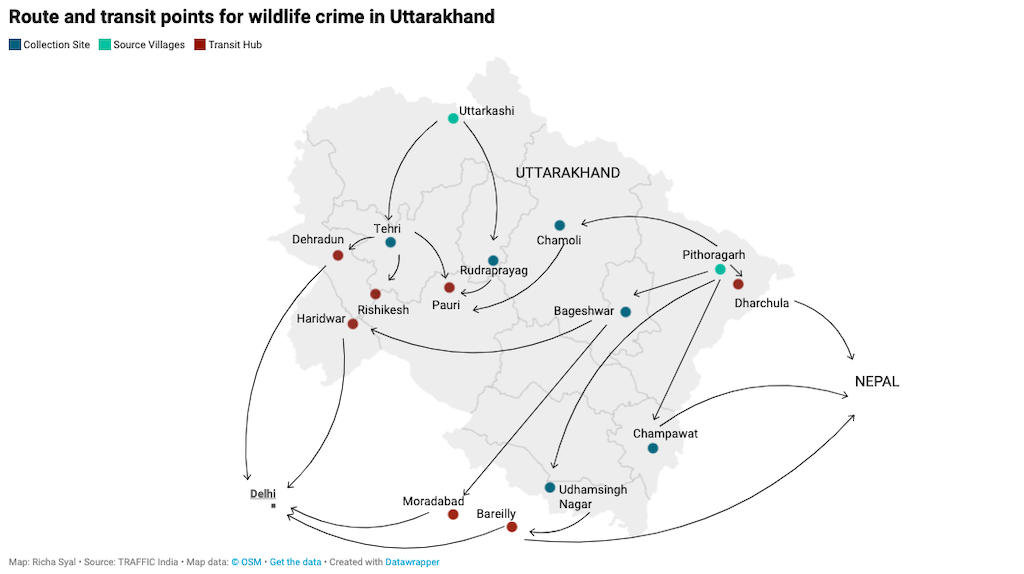

Uttarakhand is vulnerable to poaching and trafficking of wildlife, including tigers, snow leopards, elephants and musk deer. The Uttarakhand Forest Department, in association with Traffic India, has identified hotspots, source villages and local-national-international transit routes for wildlife crime in the state.

Villages adjoining the Gangotri National Park in the Uttarkashi district have been identified as sources of wildlife contraband, and so have villages situated around the Lipulekh mountain pass near the Chinese trading town of Taklakot in Tibet. Both these areas are close to the snow leopards’ habitat and the cats are often seen here at altitudes below 2,600m in the winter season.

The Traffic report identifies collection sites of wildlife contraband in the districts of Champawat, Udhamsinghnagar, Bageshwar adjoining Pithoragarh, Chamoli, Rudraprayag, Pauri and Tehri adjoining Uttarkashi. From these collection sites local transit points include Dehradun, Haridwar, Bareilly and Moradabad, which lies in Uttar Pradesh. The national transit point to Delhi is located about 200km away from these local transit points.

Champawat, Dharchula of Pithoragarh, Udhamsinghnagar and Bareilly all share an international border with Nepal. This entire area is identified as a hub of international wildlife trafficking routes.

Uttarakhand shares a border of about 275km with Nepal on which there are eight formal routes of movement. Though the Kali River forms the border between the two countries, it remains unguarded.

Chandan Singh, Station Officer at Pithoragarh Police, said people cross the Kali River by swimming and using tyre tubes. He said it is not possible to guard such a long, open border.

According to Saket Badola, head of Traffic India, “Targeted poaching of snow leopards does not take place as the animal is not easily accessible, but opportunity killing or trading can be done. If the hunter of common leopards comes to know about the presence of a snow leopard or gets the information of a dead snow leopard, then they try to kill or sell it.”

Bagori village in Uttarkashi, where snow leopards are reported to have attacked livestock ‘some time back’. Photo: Varsha Singh

In the villages

Bagori village in Uttarkashi district is mainly a village of cattle herders of the Bhotia tribe. The sheep herders go with their livestock to the Nelang valley along the Chinese border during the summer. The villagers of Bagori also contributed to establishing the Indo-Tibetan market in Nelang before 1962.

Rajendra Singh Negi, a herder from this village, has been taking his flocks to the Nelang-Jadung area near the Chinese border since 1972. After staying around Nelang from June to August, he returns to Bagori in September every year with about 400 sheep and goats.

“The snow leopard has attacked some animals of the village some time back,” Rajendra Singh said. “We get to know its presence by the way it hunts. He kills many animals at once. Snow leopards are very difficult to see.”

He denied hunting this snowy creature: “No one can go there to hunt him. There are army checkpoints everywhere. The Nelang-Jadung area cannot be visited without permission.”

Mohan Singh, a farmer from Sukhi, a village based below Harshil, said: “We feel the presence of snow leopards in the meadows above the village during winters.” But he was reluctant to comment on hunting. “If the dependence of the people on the forest is to be reduced, then an arrangement about their employment has to be made,” he said.

Herder Rajendra Singh Negi has been taking his flocks to the Nelang-Jadung area near the Chinese border since 1972. Photo: Varsha Singh

Camera traps

Madhavendra Singh Rawat, head of the forest panchayat (village council) of Harshil village, adjacent to Bagori, said when an attempt was made to install camera traps in some villages close to the Gangotri National Park to monitor wildlife, the villagers resisted. If the villagers see the cameras, they uproot them and throw them away.

“There are two difficulties in installing camera traps in villages in the high Himalayan region,” according to Tito Joseph, the programme manager at the Wildlife Protection Society of India. “The first is related to conflict and the second is to hunting.”

“We have seen cases of snow leopards being poisoned by villagers when they attack their animals. In the case of hunting, hunters from outside contact the local people. No outsider can hunt here without the help of a local person,” Rawat said.

“We have found that outside hunters tell the local villagers that if they can catch this animal or find its carcass, then they give them its skin and nails and in return they will get money. It is possible that due to these reasons most of the villagers do not want to allow camera traps to be installed. Nor do they want to talk about hunting. It is very important to develop local intelligence to gather information on this.”

Joseph said that demand for skins, bones, nails and other parts of tigers, snow leopards and other wild cats comes outside the country. “There is an international trade and market for illegal wildlife. So we cannot say that the snow leopard or other wildlife animals are not being hunted. But we do not have the data for this.”

Saket Badola, from Traffic India, reiterated the same point.

Conviction rate

The biggest problem with wildlife crime is that the conviction rate is low, Joseph said.

Under the Wildlife Conservation Act, there is provision for imprisonment of three to seven years in jail, and/or a fine of up to Rs10,000 (about US$134), for wildlife crimes. Out of the court cases involving snow leopards registered in Uttarakhand since 2000, only one conviction was secured in 2012 – and the accused were later acquitted by a higher court.

The case involved two people arrested with snow leopard skin from the Dharchula area of Pithoragarh on March 24 2012. The accused, 31-year-old Sukhraj Danu and 25-year-old Manoj Agari, were arrested by the SSB and were both found guilty by the Didihat Trial Court.

The Didihat magistrate sentenced them each to three years’ imprisonment and a fine of Rs10,000. However, they appealed in the Higher Pithoragarh Sessions Court and were both acquitted.

'The most important gap is that there is no central database as far as snow leopard illegal trade is concerned.' Photo courtesy Aishwarya Maheshwari

Central database

“We don’t have enough and substantial information. The most important gap is that there is no central database as far as illegal snow leopard trade is concerned,” said Aishwarya Maheshwari, who worked with Traffic India as a lead researcher in a study of the illegal snow leopard trade from 2003 to 2014 and presented his findings at the 2017 Global Snow Leopard Forum. Currently he is working as assistant Professor, Wildlife Sciences at the Banda University of Agriculture and Technology.

His study, covering 11 out of 12 snow leopard range countries in Central and Southern Asia, barring Kazakhstan, reported 439 snow leopards in illegal trade from 2003 to 2014. This represented a loss of approximately 8.4% to 10.9% of the snow leopard population, assuming a mid-point population of 5,240 to a minimum population of 4,000 individuals. In this finding India recorded seven cases of snow leopards in the illegal trade.

“All the snow leopard host regions in Central and Southern Asia are united for protection of the snow leopard under CITES,” Maheshwari added. CITES, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species, is a global treaty for regulating international trade in endangered and vulnerable species, and now has more than 180 signatories.

“Under conference12.5 [in 2002], all the parties are mandated to report any kind of illegal snow leopard trade incident in their country to CITES so that a central database can be maintained,” Maheshwari said. “It would be helpful not just to look at what is currently happening but how the trend is going.”

Varsha Singh is an independent journalist currently based in Uttarakhand. This investigation is part of a series on illegal trade of snow leopards, supported by Oxpeckers Investigative Environmental Journalism and the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organised Crime, and is published locally by The Third Pole here.

• Use our #WildEye Asia tracking tool to find details on snow leopard and other environmental crimes