05 Nov China’s snow leopard crimes

China is the biggest market of illegal trade in snow leopards. A data investigation by Hsiuwen Liu uncovers a recent decline in related crimes, but indications of organised trafficking in the rare cats

A snow leopard skin spotted by EIA investigators in Linxia in 2016. Photo courtesy Environmental Investigation Agency

Covered in thick white fur with black spots, snow leopards live in some of the highest mountain ranges and plateaus across Central and South Asia. There may be as few as 3,920 to 6,390 snow leopards remaining in the wild, though the actual number remains unknown, according to the Snow Leopard Trust, a Seattle-based organisation working to protect the endangered animal.

Among the 12 range countries, China is home to the world’s largest snow leopard population. Research shows 60% of the world’s snow leopards live on the high mountains in China, primarily throughout the Tibetan Plateau and on the northern side of the Himalaya.

China is also the biggest market of illegal snow leopard trade, according to research by the global wildlife trade monitoring group Traffic.

“Snow leopard body parts are used for multiple different purposes in China,” said Debbie Banks, who leads the tiger and wildlife crime campaign at the Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA).

“There is a more localised market in Gansu Province for snow leopard skins to be used for making waistcoats, but across the country there is a demand for snow leopard skins as decorative items, such as home decor for the floor, the walls, the sofas. They are also made into taxidermy specimens. Snow leopard bones are also used in traditional medicine.”

This demand puts further pressure on the population which is already facing rising threats due to habitat loss, climate change and retaliatory killings as a result of human-wildlife conflict.

Organised crime

For a long time, researchers and conservationists have been trying to study the scale of snow leopard poaching and trafficking in China. In 2014 Dr Li Juan and Dr Lu Zhi, both with the Center for Nature and Society at the College of Life Sciences at Peking University at the time, identified 43 snow leopard poaching and trade cases in China from 2000 to 2013, involving at least 98 snow leopards.

Traffic reported in 2016 that 221 to 450 snow leopards may have been poached and entered illegal trade annually since 2008, and that China has by far the largest estimated number of snow leopards poached – 103 to 236 per year.

More recent figures on the illegal trade of this elusive and shy cat are not available. However, by building on existing studies and reviewing records of China’s snow leopard-related convictions and seizures, an updated data investigation by #WildEye Asia found that in the past two decades, a minimum number of 354 snow leopards were poached and traded in China.

The data shows a declining trend in overall snow leopard crime incidents. The total number in the first one third of the analysis period (2001-2007: 161) was 2.5 times higher than in the third (2015-2021: 63). However, large seizures that involved more than three snow leopards were made until 2017, indicating that organised illegal trade still continues to happen in the country.

Banks and her colleagues have been trying to piece together the network of traders operating in China since 2005. From Linxia, Gansu, once a trading centre for animal skins, they found a loose, adaptive network of criminals operating from South East Asia, all the way over to the eastern seaboard of China.

“I would say it’s organised as it is transnational, and it is organised in that there are networks or individuals within the networks that have roles to play from procurement, logistics, transport, processing, wholesale and then retail,” Banks said.

Snow leopard skins used to make waistcoats for sale in a local marked. Photo courtesy WPSI/EIA

Trade hubs

Located in the upper reaches of the Yellow River on the southwest of China, Linxia Hui Autonomous Prefecture was a famous commercial hub on the ancient Silk Road. It has been called the “dry port of the west”, and has kept intact the heritage and skills of processing animal skins.

It was home to a famous fur market where EIA surveys in 2005 counted 60 snow leopard skins. The largest known seizure in China of 27 skins was also made 2007 in Linxia: a man named Ma Ha Lu Na confessed that he has bought more than 30 pieces of snow leopard, clouded leopard, lynx skins and other protected wildlife products ranging from 1,200 to 2,000 yuan between November 2006 and July 2007, and had sold two snow leopard skins for 4,000 yuan each.

When Banks and EIA’s investigators arrived at Bei Da Jie Market in Linxia in 2005, there were more than 100 shops selling furs. “Everything was just openly displayed in the shop front but also on the street, you could literally, like going to buy vegetables, walk down the street and on both sides of it, snow leopard was very openly sold,” Banks said.

From 2005 to 2012, EIA’s investigators uncovered 100 snow leopard skins for sale across western and central China, particularly in Linxia. Traders indicated that the skins were sourced from China, Mongolia, India, Nepal and Pakistan.

Banks said while the scale of recorded open trade has declined over the years because of law enforcement activities in the region, the trade continues in a less public fashion. Seizures with links to Linxia were still made up until 2017.

“It wasn’t really distracting the networks. Trade became a little bit more discreet,” she said.

Data investigation

The data investigation by #WildEye Asia also confirmed that illegal trade continued in Linxia after 2012.

In one particular case, a suspect named Bi Chengming sourced snow leopard skins in Linxia three times between October 2013 and July 2014, and travelled to Urumqi on a passenger shuttle bus to sell the skins to Mu and Yi. Mu and Yi later sold the skins to their local contacts, Wu and Xie. Eleven snow leopard skins were involved in this case, while more snow leopard products were confiscated during the investigation. Bi was sentenced to 7 years in prison with a 50,000 yuan fine.

Today, Bei Da Jie Market is a bustling commercial street selling clothing, tourist souvenirs and local snacks. The fur market was closed down, but research led by Dr Xiaoyu Li and Dr Lingyun Xiao at Peking University showed that the level of poaching in the province still remains relatively high, with secondary poisoning and trapping continuing to pose threats to the snow leopard population in the region.

“I think the enforcement or the level of investigation today from some of the Chinese authorities is more effective than it was back then, but they haven’t disrupted the networks that are operating across land borders,” Banks said.

Cross-border trade

The investigation into traders in Linxia brought EIA’s team across the province to Xining, Qinghai, down to Lhasa, Tibet, and then across the border to Kathmandu, Nepal.

In the past decade, Chinese footprints have consistently expanded in Nepal – China overtook India as the biggest foreign direct investment source for Nepal in 2014, and has since then topped the chart in terms of pledges.

In tourism hubs like Thamel, for example, Chinese tourists have overtaken European backpackers as the majority demographic. Tea houses, hotels, telecommunications businesses run by Chinese nationals began to flourish, transforming Thamel into a mini-Chinatown. Chinese nationals have also been involved in gambling and illegal wildlife trade that operates from Thamel.

“What we’ve documented is a close-knit community network who are involved in procuring wildlife parts for traditional Chinese medicine," Banks said. "They have the logistics in place to move wildlife from and via Nepal to Tibet, and into the wholesale markets and trading hubs such as Shigatse, Lhasa, Xining and Linxia.”

Banks said Chinese nationals they encountered at Kathmandu in Nepal were involved in tiger, leopard, snow leopard, musk, bear, pangolins, rhino, ivory, even seahorse trades. Many of them are buyers and people with licences to trade in yartsa gunbu trade, a caterpillar fungus that’s highly prized for traditional Chinese medicine. They are also trading orchid species and other plants and fungi.

“That provides them with the logistics and the transport networks to move wildlife across borders. They are connected to individuals that we’ve documented offering illegal wildlife in Shigatse, Lhasa, and Linxia. From Linxia that network runs on through Hebei, Hangzhou, essentially to anywhere in China where somebody wants a snow leopard skin as a decorative item,” Banks said.

Snow leopard claws were sold in a market in Urumqi. Photo courtesy Ma Ming

Court verdicts

Investigations into court verdicts by #WildEye Asia found nine smuggling cases in the past two decades that came from Mongolia, through border ports and road checkpoints into Inner Mongolia, China.

In most of the cases, snow leopard skins were smuggled across the border by a Mongolian citizen to Chinese contacts in Inner Mongolia for sale. They either hid the snow leopard skins on themselves, or in the hidden compartments of their cars.

Similar findings were also made by Ma Ming, a retired scientist from the Xinjiang Institute of Ecology and Geography, Chinese Academy of Sciences. From 2002 to 2012, he and the Xinjiang Snow Leopard Team collected poaching and trade information on snow leopards through site visits and market surveys in China.

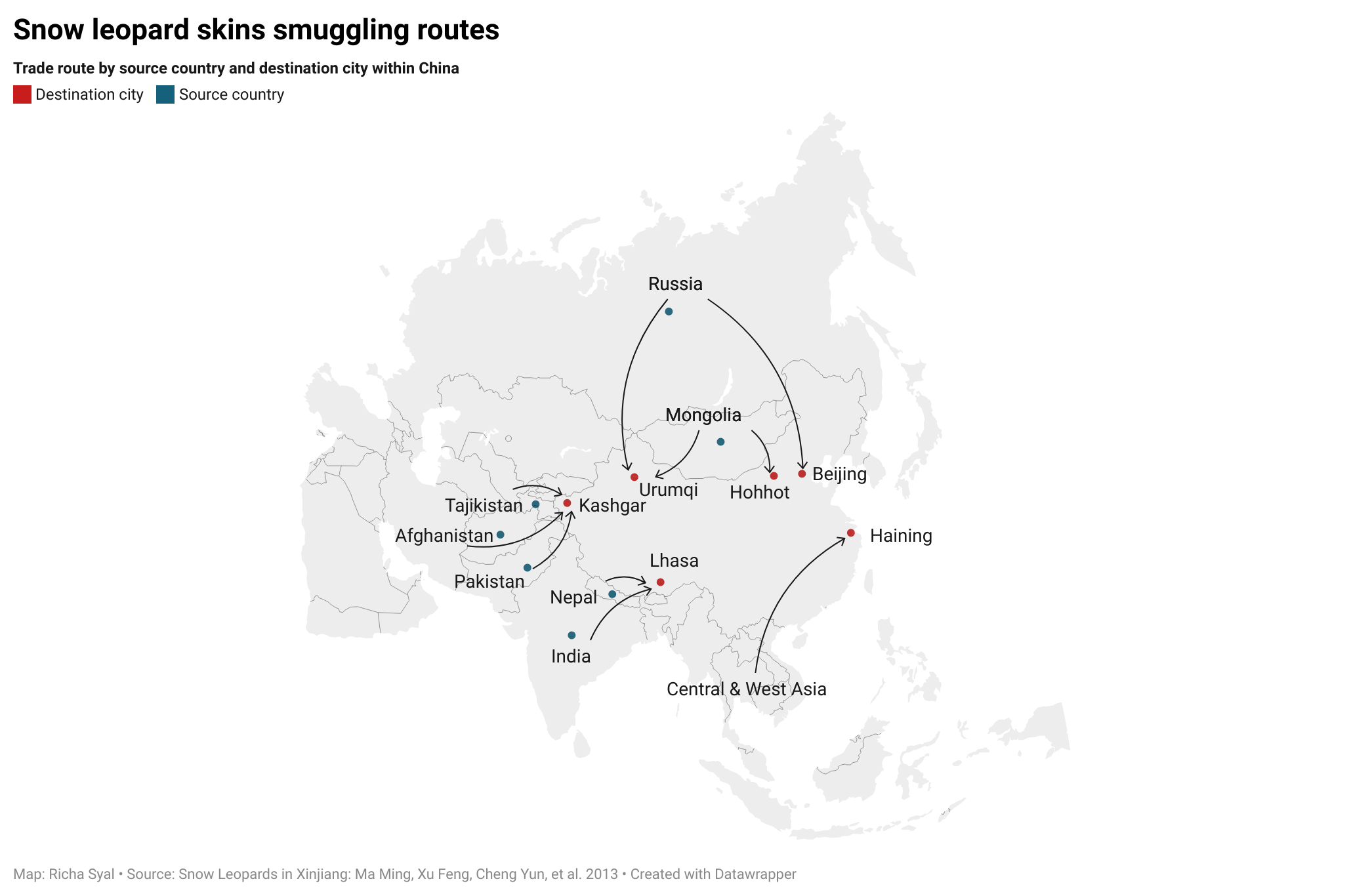

The team identified four major trade routes of snow leopard products in the country: from Central Asia to Xinjiang, together with locally poached products, to the east coast of China; from Qinghai-Tibet area to Sichuan, Gansu; from the southwest of China to the East; and trade routes in northern and northeastern Inner Mongolia, mainly with sources from Mongolia and Russia.

“Border controls are relatively loose in these border areas, some people just wear the fur on themselves when they cross the border,” Ma said. “The products ended up in trading hubs such as Urumqi and Kashgar, where we have seen snow leopard skins, bones, claws and other products for sale in the market.”

Aishwarya Maheshwari, a wildlife biologist who used to lead the snow leopard illegal trade project with Traffic in Central and South Asia, said in general snow leopard parts enter trade through three different forms.

“One is retaliation killing, two is incidental catch – meaning the snare or trap was laid to catch other species but a snow leopard was caught – and three is done by very well-organised syndicates behind the snow leopard illegal trade,” said Maheshwari.

In the Traffic report, the team also identified multiple cross-border trade routes through interviews with local experts, including the Nepal and Mongolia routes mentioned by Banks and Ma.

“Snow leopard illegal trade is not a within-country affair, it is a cross boundary affair, and if you really want to achieve conservation goals, then you have to work collaboratively across countries,” Maheshwari said.

This investigation by Oxpeckers Associate Hsiuwen Liu is part of a series on illegal trade of snow leopards, supported by Oxpeckers Investigative Environmental Journalism and the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organised Crime.

Use the #WildEye Asia tool to track snow leopard and other wildlife trafficking court cases